Catching up with VSimulators, Exeter’s new outstanding VR facility

AMTI

Located at Exeter Science Park, the University of Exeter VSimulators facility is a new ‘super force plate’ which can recreate any environment either physically or virtually, immersing up to nine research volunteers in a simultaneous experience.

Unique within the UK and potentially the world, Summit Medical & Scientific spoke to members of the VSimulators team in a two-part series to find out more about their work and how they use technology at their innovative new facility, including:

Professor Sallie Lamb, Mireille Gillings Professor of Health Innovation:

“I am a physiotherapist by original training and then a statistician, so my interests are quite broad ranging. My primary interest is older people, and particularly looking at new interventions to prevent falls in older people. This is a massive public health problem all over the world. We want to do a whole new program about understanding what actually happens when an older person is falling. We know that, if we measure someone, that we can predict with modest precision whether they will fall over within a year, but that’s not the same as studying what’s actually happening in their body at the moment that they fall. What exactly is going wrong? As a consequence, we are not very precise at treating it. We want to use VSimulators’ force plate and VR technology to have a much better handle when we fall.”

Dr Genevieve Williams, Lecturer in Sports Biomechanics:

“My interest is motor control and biomechanics, looking at how we typically perform everyday actions such as standing and walking and how that varies if we change health status.”

Dr Hannah Rice, Senior Lecturer in Biomechanics:

“My main focus is on overuse injuries. Typically, I work with healthy populations such as runners and military recruits to understand the risk of overuse injuries and stress fractures. I’m also interested in working with orthopaedic surgeons to understand how gait is influenced by a joint replacement, such as hip or knee replacement surgery.”

Dr Sharon Dixon, Associate Professor in Biomechanics:

“I’m keen to keep a focus on sport, looking at characterising complete sports movements such as on a tennis court or squash court – run, stop, turn, jump, etc. My current project is with older adults, allowing realistic simulation of typical sports movements in the older population.”

Julie Lewis-Thompson, Commercial Manager:

“Alongside these innovations and research projects, there’s a really big commercial aspect to VSimulators. We are an academic and VR based research facility first and foremost, but we are also really keen to engage with commercial organisations around that innovative development space.”

![]()

Congratulations on the recent opening of your new facility. What is the background to the facility, and what is the vision for it?

Julie: “Originally VSimulators started off as a multidisciplinary conversation, predominantly from people with a civil engineering and structural engineering perspective. There’d been a lot of research into understanding what causes buildings to move and how they move, but very little understanding as to the impact on human occupants. A research event in 2015 culminated in this idea of building two facilities, one at Bath and one at Exeter, to enable the opportunity to replicate building motion and seek to understand the human responses within that environment. And as the conversation evolved, we realised there was an opportunity to reach out with healthcare professionals, too. The Bath facility was opened in October 2019, and the Exeter facility opened this year.”

Could you tell us about the technology you are using, and how you are using it?

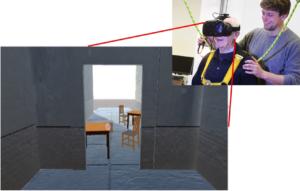

Julie: “We have an 8m x 8m chamber, and within that is a 4m x 4m Octopod motion platform which can move on six degrees of freedom. Across this motion platform we have what we believe is the world’s largest array of custom-made AMTI force plates. This array creates one giant force plate to deliver a fully instrumented floor, capable of comprehensive data capture and analysis. We can also simultaneously immerse up to nine occupants in a virtual environment using VivePro headsets, which correlates with the motion on the floor. Full motion body capture is available through a body suit supported by an array of 16 cameras. This enables the capability to feed data in from existing environments, and then extract data in terms of human responses in reaction to that environment. This information is then synchronised frame by frame and presented to the research team for analysis.”

Genevieve: “There’s two key aspects of VSimulators which make it really special. The first is the nine AMTI force plates mounted on a motion base surrounded by the 8x8m motion capture area, which allows us to have people performing talks such as walking in a relatively free environment while we track their biomechanics and their reaction to the motion platform. The second is the integrated VR headsets and VR environment meaning that we can also control aspects of visual perception in relation to what’s happening on the ground. You can then quantitatively capture movement and different forces as people walk, stand etc around in that environment. That’s really unique.

“We’re doing a few studies with this. Firstly, I’ve got a group looking at some basic science questions. How do we control balance on moving platforms? How do we control walking when there are oscillations of the floor? We know that, for example, my hand looks like it’s still but it’s not actually still. It’s oscillating at a really high frequency and low amplitude, and we have a similar phenomenon with your centre of pressure when you’re standing up. What is the kind of stochastics, and what is the randomness of that oscillation, in normal everyday standing on a flat hard surface? And how does that change when you input a mechanical and very structured deterministic oscillation of the floor? Does the human body, which is naturally quite stochastic, link up with that deterministic floor structure or does it remain stochastic? And are there any breakpoints, where you can’t be as variable and stochastic as you’d like to be?

“The second is in development with Sallie and a number of multidisciplinary researchers, which is looking at how perception from the environment is integrated into balance control. Balance control is associated with your visual perception and proprioception, and your vestibular system. In our old motor control laboratory we had moving room illusions, where the walls tip and you suddenly step back because your vision told you that the reference has moved. You can do the same with the surface you are standing on, where you stand on different tilted surfaces but don’t visualise the surfaces. As you can see, that’s quite a clunky experiment and you need some quite specific environments to do so. The amazing thing we can do now with VR headsets and moving floors is disrupt the visual environment from the physical environment and see the effect on balance. The result is to further understand, identify the extent to which people are relying on visual information or how much they rely on their proprioceptive or vestibular senses.

“The third study is about stability, and the reality of when you are standing on the 20th floor of a moving building. Does it affect you or not? I think the reality is it will affect some people. Also, if you step out of your hospital bed after an operation on the 20th floor, is that putting you at higher risk of being unstable, falling over or feeling disorientated?”

Sharon: “From my point of view, what the facility is providing is an extension of what we’ve been doing. In our biomechanics laboratory, we would typically have one traditional force platform, and I’ve done quite a lot of work looking at different footwear and surfaces. I’ve had participants, often young, healthy and elite performers, try to simulate what they would do on a tennis court or a football pitch within the confines of a laboratory. And we have carried out some data collection out and about, with pressure insoles movement analysis systems that can cope with being outside, but in general most of that type of work has been in a lab. So I’ve always been aware of two things: firstly, you’re asking people to target a force platform, and secondly you’re only collecting data from that one step. And so this facility for me is a “giant force plate” where we can capture multiple steps in different environments. At the moment I’m interested in how older people move in sport, and the range of different ways people move is unlimited. You’ve got some people who just step from side to side, and in some people, if you say “run to that point [on the force plate] as quickly as you can”, they will do it very differently. We have seen what kinds of forces are occurring when younger people turn and stop, but we can use this facility with older people to get a lot more information beyond a traditional lab with a small force plate. And we’re working with a footwear company to look at how we can apply that information to develop footwear that’s more suitable than what is perhaps already available at the moment for certain populations.

“Looking longer term, being able to simulate more closely the whole environment so we can make it look like a squash court, for example, which perhaps we wouldn’t be able to do in the same way in our lab. A good example is that we’ve carried out quite a lot of work looking at different tennis surfaces and how individuals change their movement pattern in anticipation of the surface characteristics. And one of our PhD students looked at a clay tennis court and varied the amount of clay on it, which would influence the friction and so how much sliding people were likely to experience when turning. And at one stage, she didn’t tell them, so she’d changed it between each trial and they didn’t know. It would be really nice if we could change what the whole environment looked like. I think we get a more complete picture if we could use this simulated environment. Using VR in the future, we can change what the person is seeing as they approach a turn, for example making a tennis court look like a clay court when it’s not.”

—

Click here for part two. For more information about VSimulators, please visit vsimulators.co.uk or get in touch directly at vsimulators@exeter.ac.uk. You can read the full technical specifications of the VSimulators facility here.